Ralph Arnold and a Tale of Two Chicagos

Keith Anthony Morrison

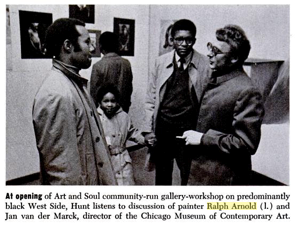

Figure 1: “He Seeks the Soul in Metal,” Ebony, April 1969.

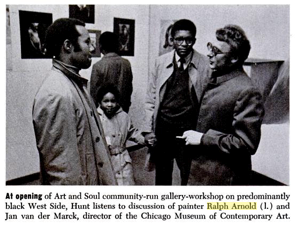

My earliest memory of Ralph Arnold is from an image that appeared in Ebony magazine in 1969 (fig. 1). He was standing with Richard Hunt, who was the first important African American artist I had heard about. Hunt had gained a national reputation in the mid 1950s, and like artists in the city, I admired him greatly. At that time African American artists were yet to be written about in art history books and hardly ever appeared in art journals or even newspapers. So when I saw the photo of Hunt with someone named Ralph Arnold I was intrigued. It appeared that they were the two most important African American artists in the city. I knew Richard Hunt; I wanted to meet Ralph Arnold. So I sought Arnold out and we became friends.

For artists in Chicago in the 1960s and ’70s, much of the action was on the North Side, but the lines of racial segregation where strongly drawn in the city. To see a person of African descent visiting a North Side art gallery was rare, and to see one exhibiting there was rarer still. With his lofty status, Hunt exhibited preeminently not only at the Art Institute of Chicago but also at the prestigious Holland Gallery. Regardless of Hunt’s race or status, his art was so well-received that he may have been the only local artist that Bud Holland exhibited at his gallery. Like Hunt, Arnold was also exhibiting on the North Side at the Benjamin Gallery, one of the most important galleries on North Michigan Avenue. As it turns out, Arnold and I overlapped with one another at the School of the Art Institute in 1959–60, but I didn’t know him then because he was taking classes part time and soon started working full time as an artist.1

Even though he was well-established by the time I got to know him in 1969, Arnold was one of the most approachable people you or I would ever meet. He greeted you with warmth and courtesy, with a twinkle in his eye, and gave you the feeling, every time, that knowing you was his gain. In the many years I knew him, bumping into him on the street, seeing him in galleries, at receptions, with his partner Bill Fredrick at symphony concerts or in their home in Old Town, Ralph’s kind and generous personality was always uplifting. I spoke to Ralph and Bill by phone a few months before Ralph’s death in 2006, and Ralph was as cheerful and positive as ever. Even in what must have been his deepest adversity Ralph cheered you up and made you feel better about yourself. African American culture and society play a major role in Arnold’s imagery, but his artistic vision was universal, incorporating white culture, American culture, and world culture as well. Nevertheless, the limited opportunities for African American artists shaped the arc of his career.

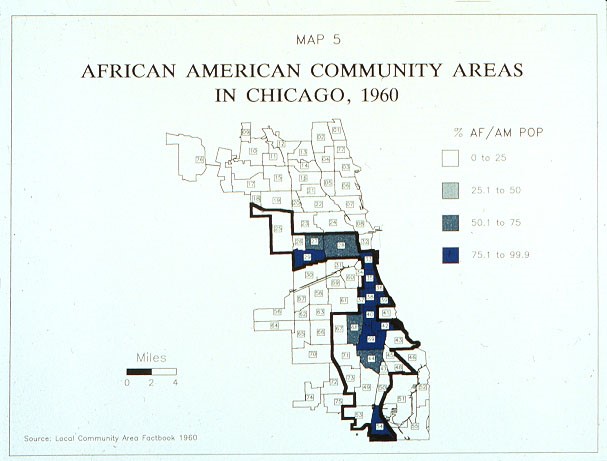

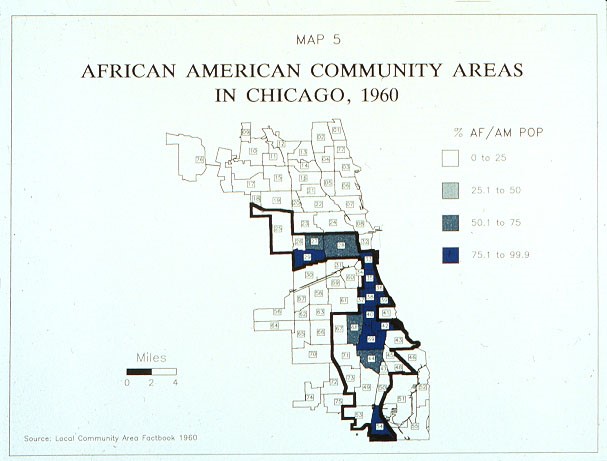

Figure 2: Map of African American Community Areas, 1960, Local Community Area Factbook (Chicago: Chicago Community Inventory, University of Chicago, 1963).

Until the Chicago Freedom Movement of 1965–67 raised the idea of “open occupancy,” whereby anyone could live where they wanted, Chicago was legally and strictly segregated, a condition that still largely persists to this day. Black people basically lived south and in a small belt on the west, and most whites lived north and northwest. East was the lake where the beaches were themselves segregated (fig. 2). Most artists wanted to live on the North Side, in Old Town, not far from the major galleries on North Michigan Avenue, but few artists of color, especially African Americans, lived there. Arnold himself lived on the South Side until 1965, when he and Frederick moved to Old Town, but he maintained close ties to the African American community on the South Side throughout his career. In fact, prior to Arnold, virtually all the students of African descent at the School of the Art Institute (including me) lived on the South Side, and outside of school we rarely socialized with the white students. Since the overwhelming number of African Americans lived on the South Side, most African American artists exhibited at one of the few venues available in the neighborhood, the Southside Community Art Center (SSCAC). A few African American artists like Arnold and me also exhibited at the Hyde Park Art Center (HPAC). While the SSCAC was a historically black institution, the HPAC was located twenty blocks farther south, across a racial and cultural chasm that felt like another country, barricaded from the largely African American poverty around it, and protected by its raison d’etre: the University of Chicago. A comparison of the two venues puts into perspective the racial divide between black and white artists in Chicago during the 1960s.

The South Side Community Center was founded in 1940 as part of the Federal Administration Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in Illinois, and its dedication was famously attended by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. It is still in its original location at 3831 South Michigan Avenue in a neighborhood of once stately mansions known as Bronzeville, which was the epicenter of Chicago’s African American community and businesses from the 1920s to the 1960s before experiencing a period of economic decline. Although not far from downtown—and in fact closer to downtown than Hyde Park—the neighborhood of the SSCAC felt like a world apart from the largely white downtown. White artists didn’t exhibit at the South Side Community Art Center, nor was it visited by the established art elite, to whom it would most likely have been unimportant, had they heard of it at all.

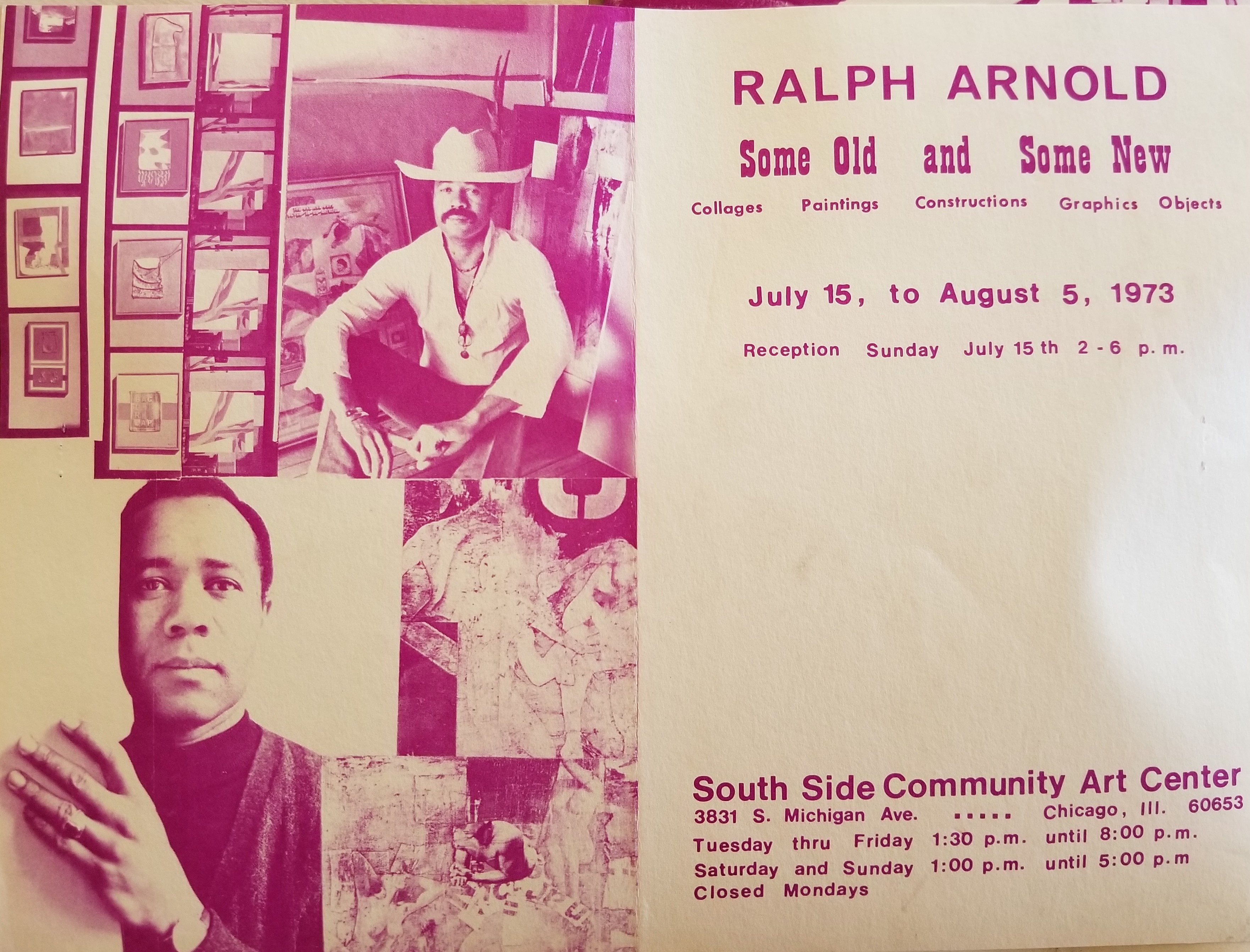

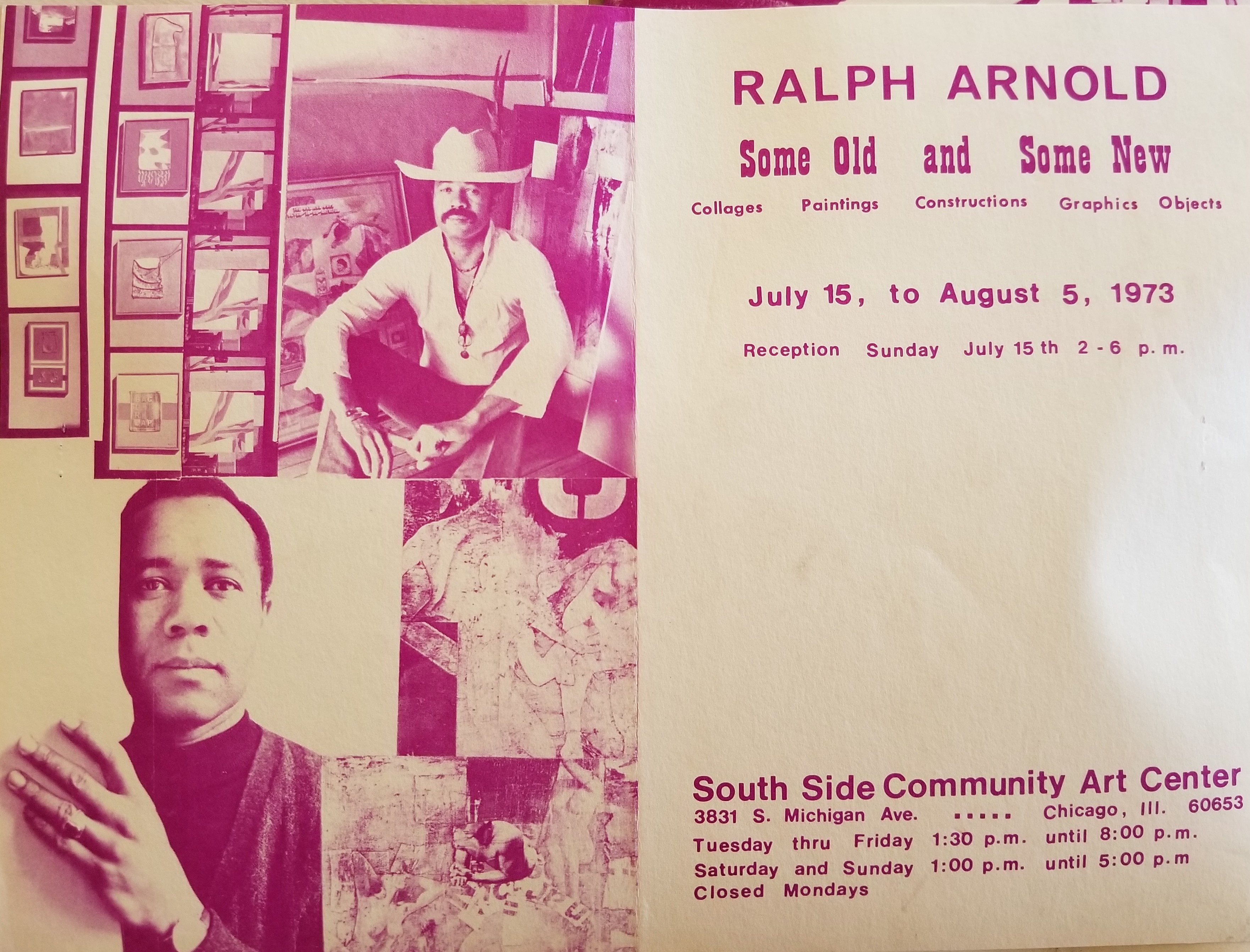

Figure 3: Brochure for Ralph Arnold exhibition Some Old and Some New at South Side Community Art Center, July 15–August 5, 1973.

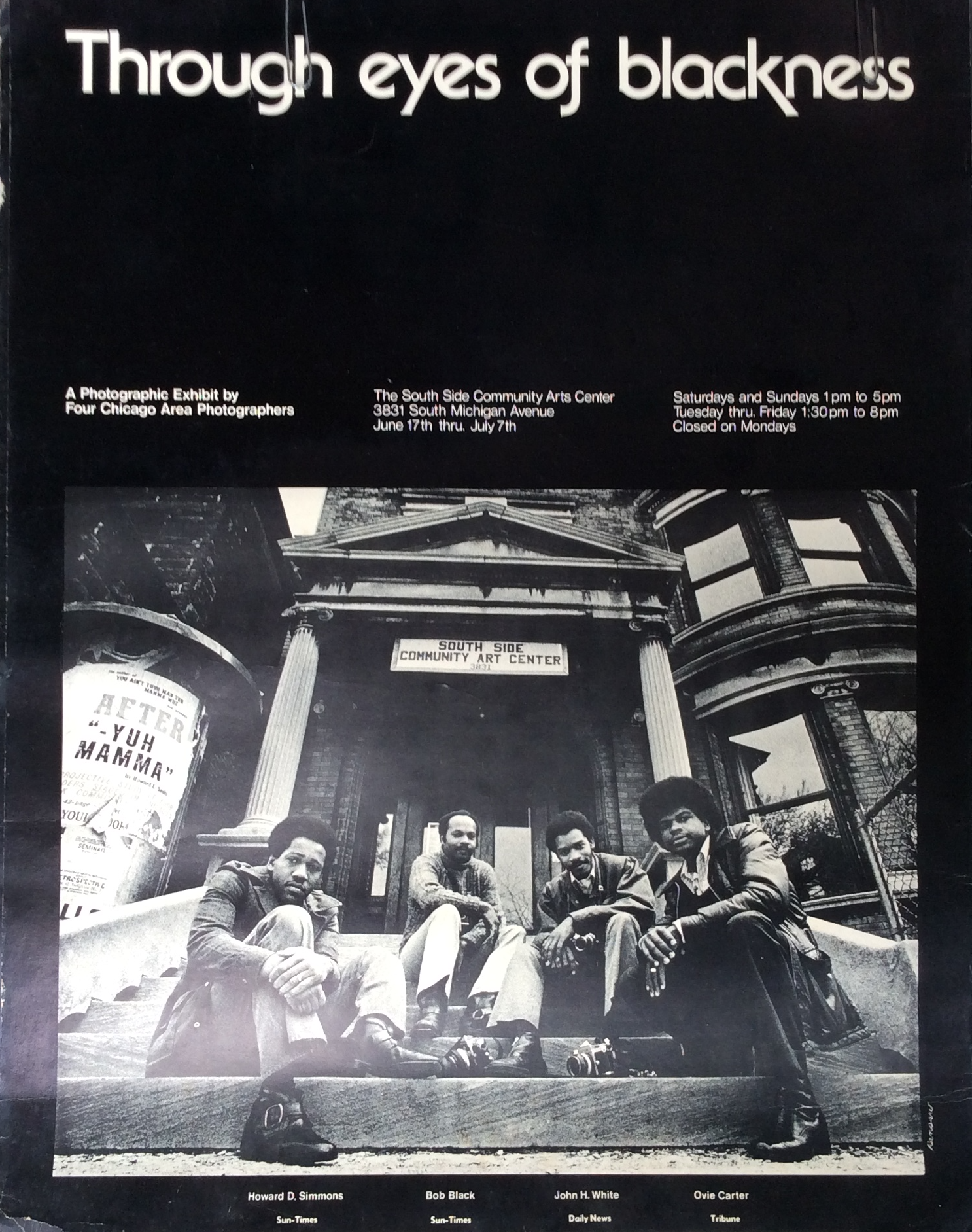

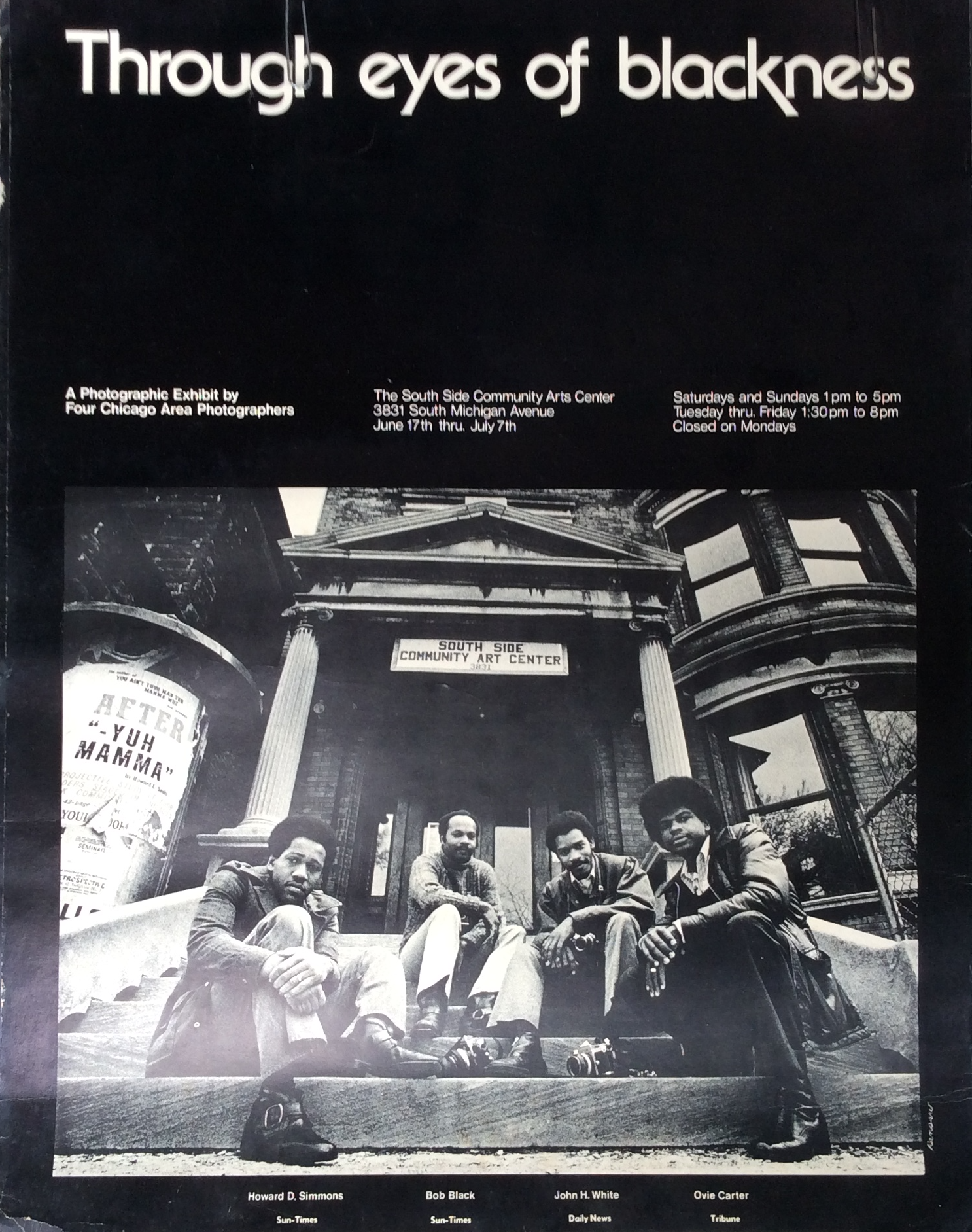

The SSCAC’s mission was to educate young African American artists and to provide a venue for them to exhibit in the absence of such opportunities in the rest of Chicago. Many hundreds of African Americans took classes at the South Side Community Art Center from its founding through the present day. Among those who taught or studied there were Eldzier Cortor, Archibald Motley, Gordon Parks, Marion Perkins, Charles Sebree, and Charles White. Arnold himself served on the board of directors of the SSCAC starting in 1974, donated works to its annual auction throughout the 1960s and ’70s, and participated in several exhibitions over the years, including his 1973 solo exhibition Some Old and Some New (fig. 3).2 Arnold surely knew artist/educator Margaret Burroughs, who was the center’s first director and remained its guiding light for decades. Also prominent among the members of the board of the SSCAC was Board President Herbert Nipson, executive editor of Ebony magazine, whose career began as a photojournalist and who told me that he admired Arnold’s work. Nipson was also instrumental in developing the corporate art collection for Johnson Publishing, the parent company that owned Ebony, and which included work by Arnold. At Ebony Nipson assigned work for African American photojournalists in the city, many of whom he knew from the South Side Community Art Center, which was a gathering place for photographers because photography was the most viable medium for African American artists seeking employment in the publishing industry. This This idea of SSCAC as a node for Black photographers may have inspired artists like Arnold to collage photographs, since photography was a medium in which there were so many notable African-American practitioners like Bob Black, Ovie Carter, Roy Lewis, Robert A. Sengstacke, Howard Simmons, and John White, all of whom were familiar faces at the South Side Community Arts Center (fig. 4).

Figure 4: Poster for the exhibition Through the Eyes of Blackness at the South Side Community Art Center in 1973. The show featured photojournalists Howard Simmons (Chicago Sun-Times), Bob Black (Chicago Sun-Times), John White (Chicago Daily News), Ovie Carter (Chicago Tribune) and ran from June 17 to July 7. It immediately proceeded Arnold’s solo exhibition Some Old, Some New, which opened July 15.

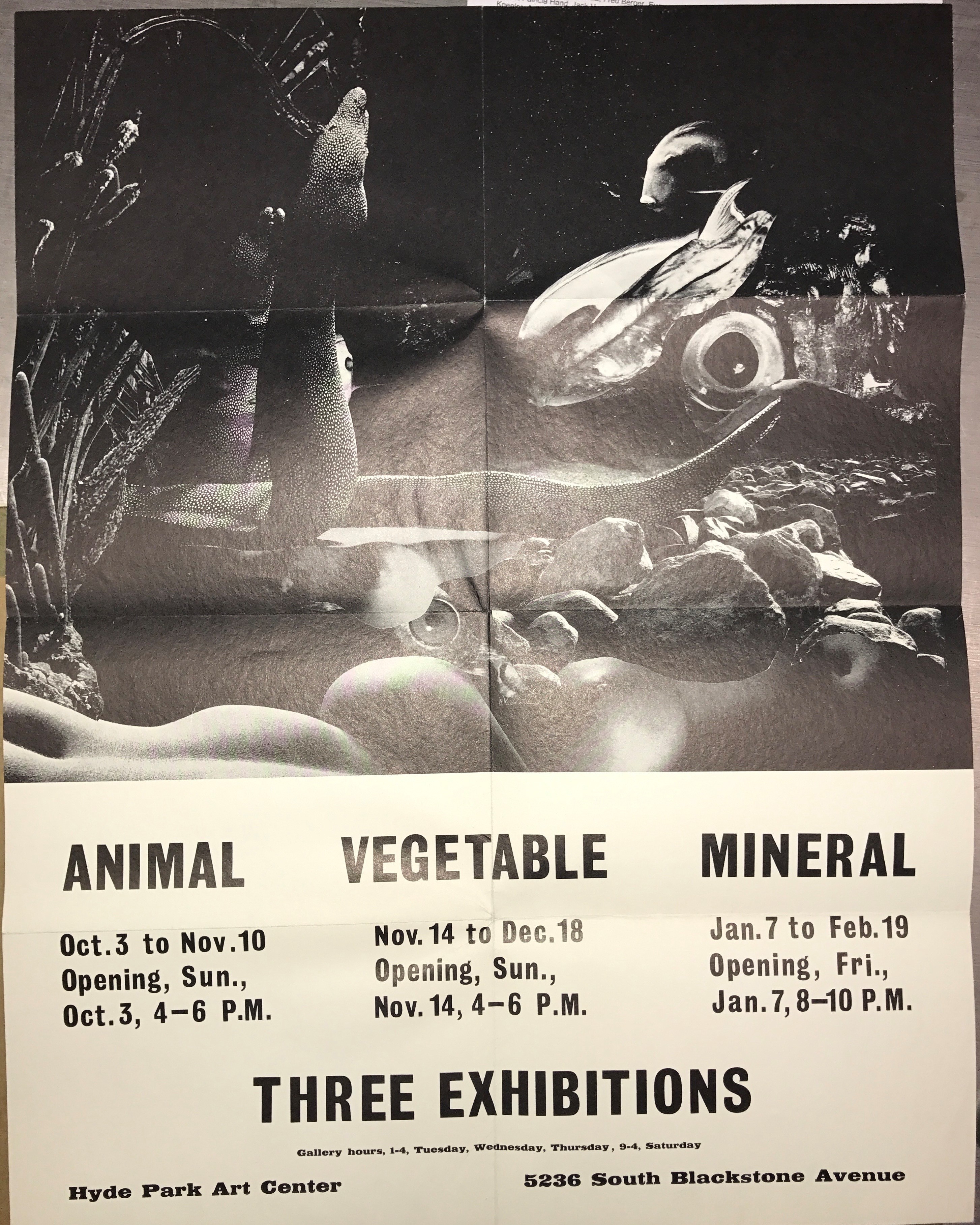

The Hyde Park Art Center was a different kettle of fish despite also being on the South Side. At that time, it was located at 5236 South Blackstone Avenue in Hyde Park, a South Side neighborhood that was a cocoon of mostly interracial people with intellectual aspirations bookended by the neighborhood of Kenwood and the University of Chicago. Hyde Park was and remains an interracial and affluent area. The director of the Hyde Park Art Center was the visionary Don Baum, who sought to create a distinct type of art in Chicago, which he successfully branded as the Hairy Who and Chicago Imagism. Arnold knew Baum quite well since he and Frederick were Baum’s tenants in the late 1950s, and I knew Don through my teaching and curatorial work.3 Although a few African American artists like Arnold and myself showed our work at the Hyde Park Art Center, most of the exhibitions there were centered around white artists from the North Side such as Roger Brown, Robert Donley, Roland Ginzel, Jack Harris, Myoko Ito, Ellen Lanyon, Gladys Nielsen, Jim Nutt (who married Nielsen in 1961), Ed Paschke, Suellen Roca, Alice Shaddle (who was married to Don Baum), Karl Wirsum, and Ray Yoshida. Gallery dealers, such as Marianne Deson, Richard Gray, and Phyllis Kind attended art events there, as did collectors such as Ruth and Len Horwich. So too did critics Harold Haydon and Franz Schulze; curators Dennis Adrian and James Speyer; and Harold Rosenberg, then a professor in the Department of Social Thought at the University of Chicago. They all were part of the city’s art vanguard elite, and they partied at the Hyde Park Art Center from the late 1960s through the 1970s.

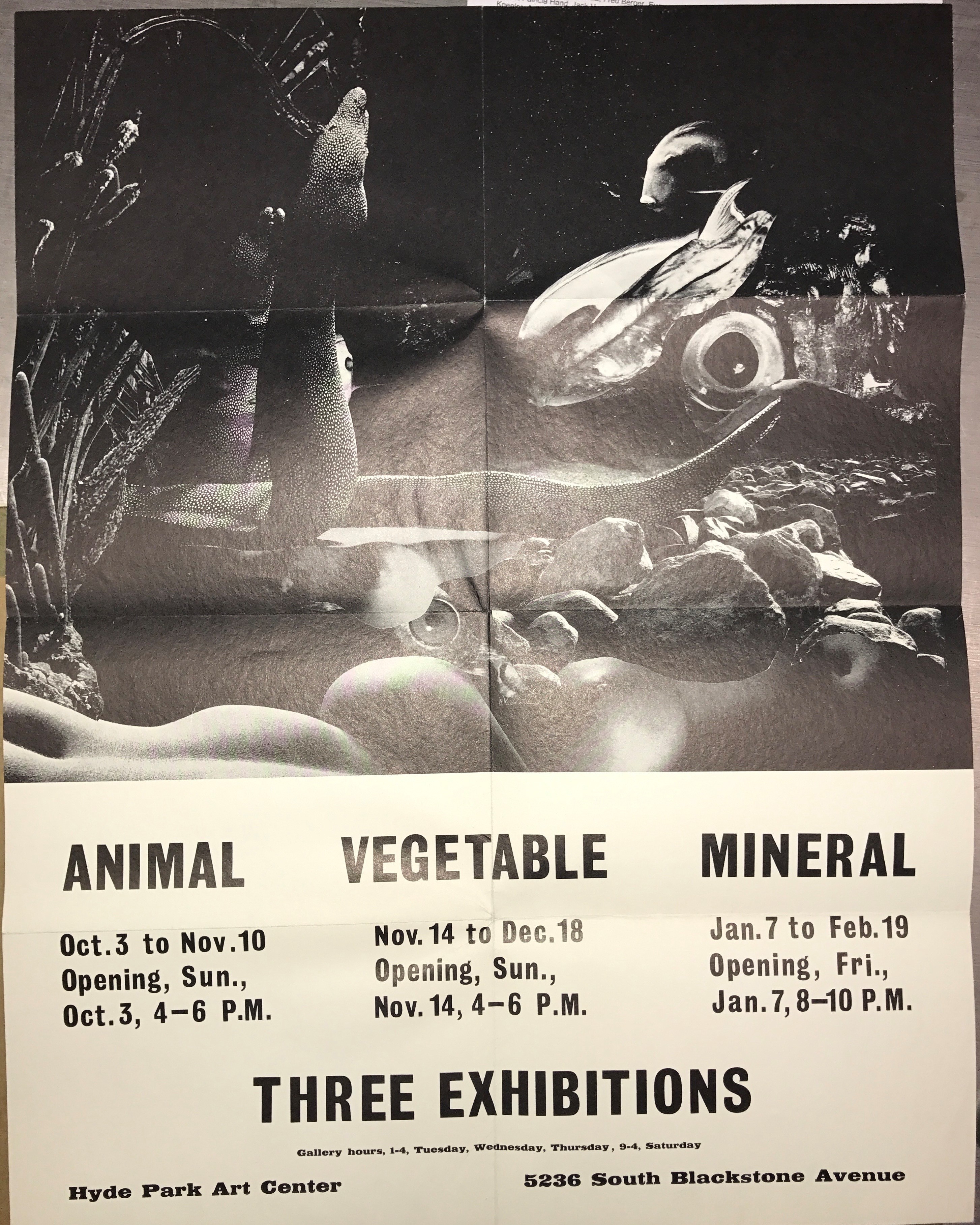

Figure 5: Brochure for exhibition Three Kingdoms, Hyde Park Art Center, October 3, 1965–February 19, 1966.

The Hyde Park Art Center served as a kind of farm system for the North Michigan Avenue galleries. The occasional African American artist in shows at HPAC, such as Arnold or me, was a bridesmaid; the white artists were the brides. Arnold showed his work in a number of important exhibitions there in the late 1950s and early 1960s, including the centennial exhibition Hyde Park Past and Present (1962) and in Baum’s infamous Three Kingdoms exhibitions in the fall of 1965. Arnold shared the same teacher as many of the Monster Roster artists (Vera Berdich of the School of the Art Institute), and critics sometimes lumped him in with Imagist artists like Nutt and Barbara Rossi because of the occasionally whimsical nature of his work.4 Ironically, even though some of the Chicago Imagists’ ideas were inspired by Joseph Yoakum, an artist of Native American/African American descent, and even though they embraced folk art in general, African American imagery generally fell outside the purview of the HPAC and the established Michigan Avenue galleries. The art of Ralph Arnold was an exception—it frequently included African American imagery in a central way through his collages that included photojournalistic images of African American life and culture (see below). If such imagery was generally frowned upon, as it seemed to me, Arnold’s art defied that discouragement. He was a universal and sophisticated mind who promoted imagery from a variety of cultures. He did not edit out his African American experiences but included them equally among others.

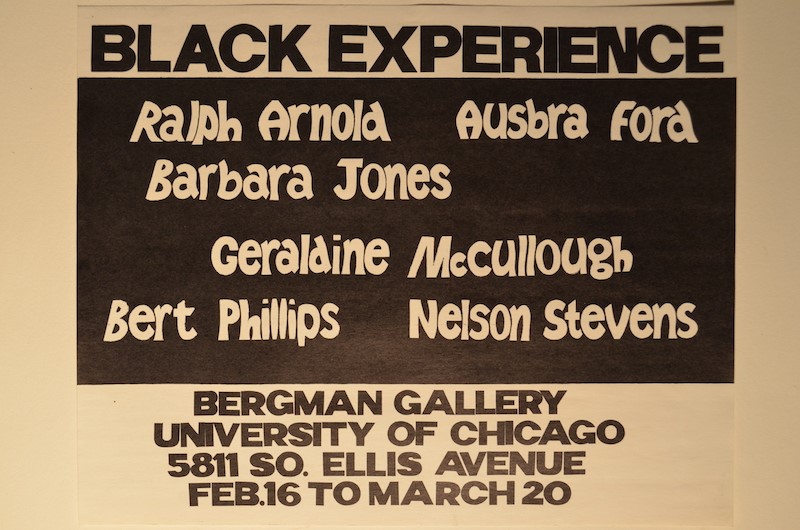

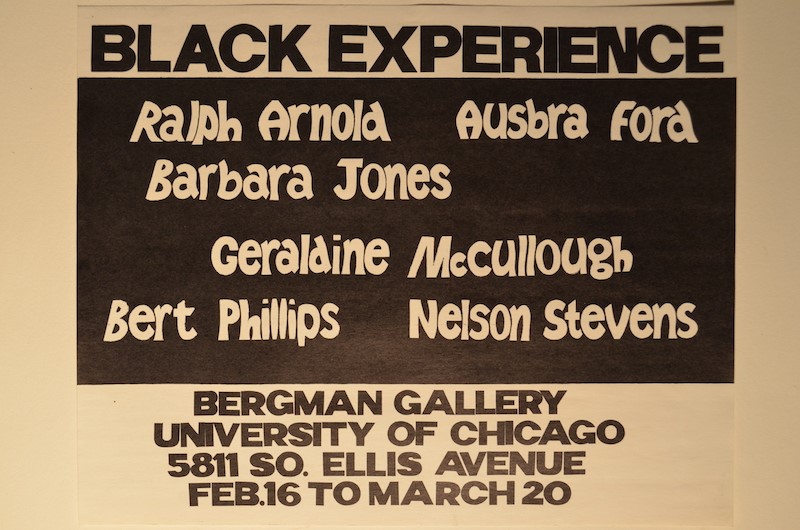

Figure 6: Brochure for Black Experience, curated by Keith Morrison, Bergman Gallery, University of Chicago, 1971.

Under pressure from the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, white institutions in the city became more responsive to exhibiting African American artists during the 1970s. The first to include African American artists in their exhibitions were mostly universities, such as Chicago State, DePaul, Loyola, Northwestern, Roosevelt, and the University of Illinois (then called the Circle campus). I was teaching at DePaul University where I curated an exhibition of Jacob Lawrence’s Toussaint L’Overture series at DePaul in 1971. In conjunction with the exhibition I wrote an essay on the exhibition for Art Scene magazine, which was published in Chicago by Dennis Stone. Having begun to develop modest credibility as a curator, I was invited to curate an exhibition at the Bergman Gallery of the University of Chicago, titled Black Experience (fig. 6). The show included several prominent African American artists working in diverse styles in Chicago at that time: Ausbra Ford, Barbara Jones (later to become Jones-Hogu), Geraldine McCullough, Bertrand Phillips, Nelson Stevens, and Arnold. Ford taught at Chicago State University and made sculptures in wood that reflected African imagery. Philips painted figurative abstractions. I had known Ford, Philips, and Jones-Hogu from our student days at the Art Institute. Jones-Hogu and Stevens were also members of AFRICOBRA, an art collective that developed a philosophy of Afrocentric art. Jones-Hogu made politically inspired serigraphs and silkscreen posters and Stevens made paintings about Black pride. The two artists in the exhibition with the biggest reputation were Geraldine McCullough and Arnold. McCullough was a nationally known abstract metal sculptor who exhibited across the country. Among her many national achievements was having been awarded the George Widener Memorial Gold Medal prize for sculpture from the Pennsylvania Academy of Art in 1964. She was chair of the art department at Rosary College, now Dominican University, in River Forest. Arnold was well established on the North Side and also had a national reputation. While neither McCullough nor Arnold needed the exposure of an exhibition of local African American artists, they benefitted from the sense of community, just like the others. It was the beginning of the 1970s and African American artists felt emboldened to assert their difference from the dominant art world and to share common cause with one another. The audience for the exhibition was almost entirely African American or from Hyde Park, which was the only really integrated part of the city.

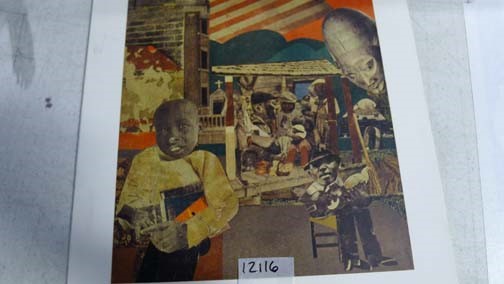

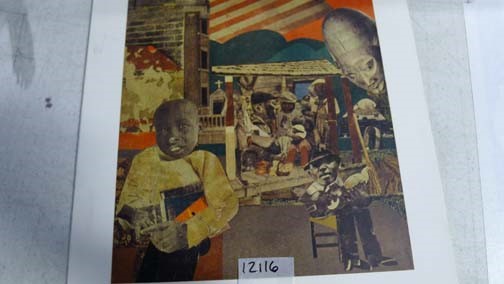

A Tale of Two Collagists: Arnold and Romare Bearden

Arnold made abstract paintings as well as assemblages with a variety of objects, but he is perhaps best known for his collages with photographs, many of which drew upon the increasing number of African American subjects featured in Look, Life, The Saturday Evening Post, Time, and African-American publications like Ebony, Jet, and the Chicago Defender. By the late 1950s collage had become commonplace in American art, and Arnold was clearly influenced by Joseph Cornell, Robert Rauschenberg, and Kurt Schwitters. But Arnold, a product of his times, was also influenced by the gestural mark-making and improvisation of Abstract Expressionism. Arnold made collages that were like scrapbooks of seemingly random events on a page that evolve and dissolve into transient abstract gestures. In his use of color, which is heavily saturated, sometimes with glossy photographs, Arnold further distinguished himself from his influences by providing a formal springboard of brightly colored pigment in parts of his paintings.

Figure 7: Color photostat of a Romare Bearden, Untitled, undated, private collection of Ralph Arnold. Chicago, The Pauls Foundation.

Arnold told me that he knew Romare Bearden and that the two of them were in touch with one another. For example, Arnold said that the School of the Art Institute had invited Bearden to teach there, but that Bearden demurred: “Why me, when Ralph Arnold lives in Chicago?” The two men were obviously collegial, with Bearden included Arnold in a lengthy history of Black artists that he wrote for the New York Amsterdam News in 1976.5 Likewise, Arnold frequently cited Bearden in his artist statements and recalled interviewing Bearden to learn more about his art, after which the older artist gave him “a little piece” (fig. 7).6

Visually, Arnold’s work clearly shows an affinity for Bearden’s work while also being distinctive.7 For example, Bearden may have used photocollages earlier and certainly was better known, but Arnold was among the first important painters to use photojournalism to imply a narrative. While Bearden tended to cut his collaged imagery into silhouettes, Arnold typically maintained the three-dimensional illusion of the photograph so that his pictorial space is often deeper. In a Bearden, you are conscious of two-dimensional form and its tension in shallow space. Arnold, on the other hand, tends to present more frontal images that shift into deeper space. Bearden used photocollage like literature, telling poetic fantasies, while Arnold’s collages are closer to photojournalism, documenting immediate and recognizable events like the protests around the Vietnam War in One Thing Leads to Another (1968) (see fig. X). Arnold’s photocollages function as abstract narratives about life in his time: imagery from the street, sports, entertainment, and popular culture of the day, oftentimes with a strong focus on African American figures and cultural moments, as in works like Yeah Team (1968) (see fig. X). Whereas Bearden typically created one iconic scene within each collage, Arnold used many pictures within the space, creating a kind of notice board in which fragmented images form a story. He documented events as if they were a photo album of clues, telling an urgent story through various prisms, like breaking news that is so “hot-off-the-press” it cannot be fully analyzed. His compositions appear sometimes to reference comic book panels that are akin to pulp fiction. The compositions can seem spontaneous, like random images of information that recall the chaos of modern culture and life. His paintings are not unlike how we perceive information on platforms like Facebook or Instagram, today. As such he seems to have anticipated cyberspace. In some ways, he was an artist ahead of his time.

Ralph Arnold’s supremacy as a collage artist was in large part due to his awareness that photographic media told life’s daily story with a timeliness. In a period when the art world was already littered with collage artists, his work stood out for its originality, imagination, and focus on the cultural issues of the day.

Notes

- 1. Arnold later returned to the School of the Art Institute in 1966 to take additional part-time undergraduate classes. He was admitted to MFA candidacy in 1974 and received his MFA in 1977. School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Official Educational Record.

- 2. For a full list of the exhibitions, see Rebecca Zorach’s essay in this volume.

- 3. Greg Stuart, Ralph Arnold Unmasked: From Pop to Political (Chicago: Loyola University Chicago Department of Fine and Performing Arts, 2008), 12.

- Jane Allen, “Some images of the Chicago imagists,” Chicago Tribune, April 16, 1972, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune 1963–Current file, 18.

- 5. Romare Bearden, “The Black Man in the Arts.” New York Amsterdam News (1962–1993), June 26, 1976, C7A.

- 6. The “little piece” by Bearden has not been found, but Arnold did own at least one color photostat of a work by Bearden, which was recently discovered in Arnold’s archive, The Pauls Foundation, Chicago. Ralph Arnold, interview by Larry Crowe, August 25, 2004, HistoryMakers Digital Archive A2004.145, session 1, tape 5, story 7, http://thmdigital.thehistorymakers.com/iCoreClient.html#/&i=197002.

- 7. Arnold was well aware of these similarities and differences, stating, “I started out doing collages because of Romare Bearden and my collages sometimes look like his, other times, they’re so far remote from his . . . as they get more figurative.” Ralph Arnold describes his artistic style in Arnold, interview by Larry Crowe.

Keith Anthony Morrison is a Jamaican-born artist, critic and curator. He has been professor and academic dean at several universities and art schools. His art has been exhibited internationally in galleries and museums. He represented Jamaica in the 2001 Venice Biennale. He has written articles for many publications. He was Guest Editor for

The New Art Examiner. He is the author of “Art Criticism: A Pan-African Point of View,”

New Art Examiner, 1979”; Art

in Washington and Its Afro-American Presence:1940-1970, WPA, Stephenson Press, 1985

; “The Art of Norman Lewis,”

Brandywine Workshop and Archives, 2016. As art critic he represented the USA in the 2008 Shanghai Biennale. A book about his work, titled Keith Morrison, was written by Rene Ater, published by Pomegranate Press, 2005. He holds the Jamaican national title of honor,

Commander of Distinction.