African American Visual Aesthetics

A POSTMODERNIST VIEW

Edited by: David C. Driskell

The Global Village of African American Art

KEITH MORRISON

Yet, artists of color—a group with an especially large stake in current interrogations of Western hegemony—all too often remained curiously outside the purview of precisely those critics most identified with so—called new theory.

JUDITH WILSON 1

Modernism—lets describe it loosely as the ideology behind European colonialism and imperialism—involved a conviction that all cultures would ultimately be united, because they would all be Westernized…Post-Modernism has a different vision of the relation between sameness and difference: the hope that instead of difference being submerged in sameness, sameness and difference can somehow contain and maintain one another. . . .

THOMAS MCEVILLEY 2

Does postmodernism exist outside of Eurocentrisim? Is it central to the art of people of color? Were African American artists ever closer than the fringe of modernism? At no time during the period of modern art (say, from Manet to Warhol) was there ever an African American concept that was important to the “canon.” The major African American concepts have been left below the radar of Eurocentricart. Postmodernism, the revision of Eurocentric global hegemony, is a civil war between the Eurocentric past and its present. The search for a definition of African American art opens into the reality of pan-Africanism, a concept arising from the increasing diversity of people of African descent in the United States. Today’s African Americans come from every continent. They are called “black” because the most minuscule percentage of black blood in their veins makes them so in America, where even if most of their blood is white it changes nothing (any Asian blood merely reinforces their “coloredness”). Black blood mixed with white blood is always black. Only all— white blood is white (3). “Black” or “African American” is, therefore, not a scientific distinction, not a matter of genetics, but a labeling of one’s appearance. Black is a political categorization as much as it is a racial one. Ever conscious of their common political reality, artists of any degree of African ancestry create a cultural matrix from the definition imposed on them (4).

Fragments of today’s African American art come from beyond these shores but have blended with foundations laid here early. By the first quarter of this century, threads that would weave an African American alternative to modernism were evident. One approach was to explore the African American experience from the context of Euro—American art. Henry Tanner studied and painted in the United States and France (5). He borrowed techniques from Thomas Eakins and Rembrandt van Rijn, but his subject matter and expression came from his experiences as a black man. Although he worked in France in the heyday of impressionism, he was not part of the European modernist movement. Tanner’s tack of using European technique to show African American insights has been explored by other talented African American artists. By midcentury, a number of them had created exciting alternatives to trends in contemporary American art. Among them was Richard Hunt, who achieved international acclaim in the 1950s. His sculpture shows the influence of Pablo Picasso and Julio Gonzalez. Hunt’s welded steel forms seem like drawings in space, and the designs suggest plant life. Not purely abstract like so much art of this decade, his work blends methods of modern machinery with motifs from the natural world. Hunt’s work is also related in concept and structure to West African metal works (6).

Barbara Chase-Riboud creates abstract metal sculpture of African American imagery (7). She uses the modernist medium of assemblage to create works that are reminiscent of slave—craft and fetish. Her works of the 1970s are like icons of bondage, made with rope and metal. Mel Edwards’s robust metal sculpture, Nine Lynch Fragments, is a metaphor of oppression. The works of Chase—Riboud and Edwards are related to those of other important American artists, such as Richard Lippold, David Smith, and Richard Stankiewicz. However, whereas the latter group made objects that articulated abstract spatial concepts, Chase-Riboud and Edwards, using the same welded steel, have evoked the legacy of the slaves in their work. Alma Thomas’s work matured in the environment of the Washington color school, although she was never quite a part of it. Like the color school artists, Thomas made stained paintings. Like them she relied on flat shapes of contrasting colors, arranged in bands. Yet her abstractions recall the designs of African American quilts and African fabric. Thomas’s fellow Washingtonian, Sam Gilliam, has been a more central part of the color school, from which his more recent work evolved (plate1). He recognized the oneness of pigment and canvas and changed the concept of painting from creating an illusion of a three-dimensional object to the next logical step, which was the removal of the painting from the stretcher to create a free-standing object. Gilliam’s art has expanded the scope of modernism to make the painting a cloth that itself becomes an object moving through space, like a decorative African dance costume that takes on a spirit that belles its literal reality. William T.Williams has made abstract painting with complex forms that have expanded the boundaries of both modernism and African American painting. Thomas, Gilliam, and Williams often use pattern to form part of their compositions, and their works show an affinity with African American quilts and weavings, African art, and the designs that decorate West African masks, African costumes, and African architecture (8).

The work of all of these artists shows the historical dualism of African American culture. It is European in part, even as it is African. If the work of these artists seems to relate strongly to Eurocentric issues it is the result of both influence and coincidence. Influence, of course, because they studied among Europeans. But coincidence because the European tenets of art that they learned were merely the springboard for their exploration of African styles and themes of importance to African Americans. For example, Martin Puryear’s work springs largely from Eurocentric sources, but is less traditional than those sources; and Adrian Piper’s work contrasts Eurocentric sources with Afrocentric issues. But the art of people like Tanner, Hunt, Gilliam, and Williams explores cross-cultural commonalty by using Eurocentric styles and methods. In the final analysis, the issue is not how their work compares to that of their Euro—American peers, but how much it shows the artist’s ability to create images that people from many cultures can relate to.

The Negro Speaks of Rivers

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older

than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln

went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy

bosom turn all golden in the sunset.I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Langston Hughes (9)

African American artists created their own formalism based on African culture. In the 1920s Langston Hughes in his poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” looked back to ancient Egypt as the source of black people’s culture. The importance of the African ancestral arts upon African Americans was most succinctly articulated by aesthetic philosopher Alain Locke. In a 1925 anthology of Harlem black writers called The New Negro, Locke wrote an essay called “The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts.” In it he stated that an African American art could best be formed on the foundation of the African ancestral arts (10). From then until now, many of the best African American artists have been affected by Locke’s call. The paintings Aaron Douglas created between 1925 and the Great Depression exemplify Locke’s ideas. In More Stately Mansions, Douglas’s figures appear in profile, a style that derives from the art of ancient Egypt, and his subjects are allegories of African American life (11). Jacob Lawrence learned how to use the profile view Douglas pioneered as a way to depict his own experiences, events of African American history, and life during the Great Depression (12).

Painting by the Egyptian formula of showing figures in profile in a flat space as Douglas and Lawrence had, helped to liberate African American art. Aaron Douglas began painting in the Egyptian manner, but that form freed him to explore local black American subjects. This style of painting gave artists a way to break the Euro-centric stronghold that had excluded expression about black life in art. But although they were allowed black subject matter, it had to be cloaked in an abstracted style that featured patterned, silhouetted figures. This was because the familiarity of the style to whites protected the new black subject matter from attack. As the abstracted style became freer, it became more important than the Egyptian style from which it had evolved. Artists became free to explore social issues. So it was that William H. Johnson, a highly trained Eurocentric artist, found through the flat Egyptian space a style for his folk paintings of the 1940s. The Langston Hughes poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” echoes this process. It traces the history of African American culture from Egypt to the Mississippi in a tale told not through the lens of European history,but through the stories ofAfrican American folklore.

Nevertheless, art that is rooted in the African American experience has been around for a long time. Edmonia Lewis’s late nineteenth-century sculpture, Forever Free, shows slaves breaking their bonds. Forever Free isa landmark in the expression of the psyche of the African American. So too is Augusta Savage’s LiftEvery Voice and Sing, a work that glorifies black voices and symbolizes group harmony, musically and politically (13). Richmond Barthe made realist sculptures of black heroes, such as Frederick Douglass and Henri Christophe. Painter Archibald Motley explored social satire and the role of cabaret in African American life. Motley’s figures, with their exaggerated features and gestures, inhabit a world of fantasy. Charles White expressed the pain and sorrow of African American rural life in drawings and prints.

The arts of Africa continued to spark imaginations. Romare Bearden favored West African motifs, often alternating images ofAfrican masks and photographs of African American life in his collage. He tried to find the common ground of the black experience in Africa and in the United States. In the 19305, Sergeant Johnson used West African and Egyptian styles to depict African American subjects. Elizabeth Catlett, who lives in Mexico, has transformed African forms such as Yoruba figures into African American and African Hispanic sculpture. Joyce Scott, working with nails, glass, and beads, makes African American versions ofAfrican fetishes and jewelry.

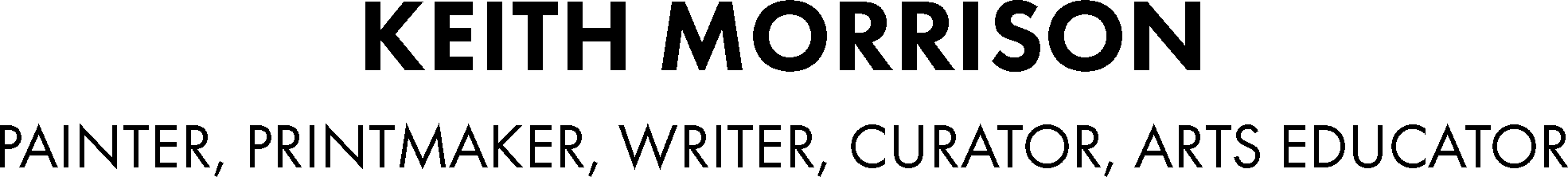

Her work also shows the influence of Pre-Columbian art (plate2). John Scott’s sculpture is influenced by ancient Egyptian crafts, tools, the papyrus plant, and the pyramids. Raymond Saunders has spliced African urban scenes to images of urban life in America in all of its multicultural complexity (plate 3). Mildred Howard creates environments from her own cultural artifacts and from symbols of religious ceremonies and other events that have been meaningful to her (fig. 1.1).

A political agenda, created by some artists during the Civil Rights Movement, informs much of today’s art. During the 1960s, public art, especially murals, gained momentum as a people’s art (14). Among the more prominent examples is the The Wall of Respect, created in Chicago, at 39th and Langley Streets, in 1967 (plates 4 and 5). It was one of many public murals painted in African American communities from Boston to Los Angeles. The Wall of Respect was a community venture, worked on by painters, photographers, printmakers, poets, including Eugene Eda, Bill Walker, Roy Lewis, Norman Parish, and Jeff Donaldson. They used images of Mohammed Ali, James Brown, Aretha Franklin, LeRoi Jones, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King to make a collage. The Wall of Respect was significant because it was created by artists who shared a common political will. It represented no stylistic continuity or harmony, but, instead, a sociopolitical collective. The Wall made political and social ideology more important than formal concerns, an idea that was not to take hold in mainstream American art for many years to come. The iconography of the Wall was public in that everyone in the black community knew the meaning of all of its parts. Perceived by many whites as cliche-ridden imagery, in fact it was a successful attempt to use popular images to reach a broader audience. Many of today’s white artists embrace this idea with no knowledge of its origin. The Wall of Respect established the concept of public art (art by fledgling artists that expresses the values of a wider public), as an alternative to private art in public places (personal art by established artists put on View in public places). Many examples of private art in public places, widely supported by our bastions of culture, including the National Endowment for the Arts, were built before that distinction became clear. In the light of today’s proliferation of murals, where many artists work outside of the mainstream to generate a wider public, The Wall of Respect stands as a land mark in the evolution of contemporary American art.

Members of the Afri-Cobra movement, founded in Chicago in 1968, also aimed for a wider public. Founders included artists Jeff Donaldson, Napoleon Henderson, Nelson Stevens, Barbara Jones Hogu, Gerald Williams, Frank Smith, Wadsworth Jarrell. The goal of Afri-Cobra was to make an art that was accessible to all black people, and that expressed the political power of a black ideology. Afri-Cobra created posters because of the medium’s low cost and ease of dissemination. They made art from magazine photographs of widely known heroes, such as Aretha Franklin, James Brown, Leroi Jones, Eldridge Clever, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King.

Afri-Cohra (which continues to produce art), makes no distinction between aesthetic and political goals, a concept that today’s postmodernists accept, but others denigrated in the 1960s.

African American artists have indicted American society and parodied their own reality. In the mid-1960s, Dan Chandler painted a number of works that condemned white America’s treatment ofAfrican Americans. His Fred Hampton’s Door is an icon of the Black Panther member who was murdered by the Chicago police (15). David Hammons has made art from a variety of vernacular African American images to satirize white America’s interpretation of black culture. His mural How Ya Like Me Now? portrays Jesse Jackson as a white man (16). Bettye Saar has created many African American shrines and has explored the socioreligious mythology of black people. Saar, Chandler, and Murray DePillars are among the African American artists who have used themes such as Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, Black Sambo, and watermelons to satirize black images that are sacred to white America but insulting to black people. Artists have also explored the indigenous experience through arts that have a wider public appeal: the blues, jazz, rap, reggae, photo journalism, the movies, and TV. Author Ralph Ellison is supposed to have said that all the paintings of Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, and Norman Lewis don’t add up to the power of one musical note by Charlie Parker. The statement, even if apocryphal, points to the relatively small impact of painting and sculpture on African Americans. The difficulty to ignite the passion of black audiences has been a historical monkey on the back of black artists. Can art by black people turn on black folks like their music? Does it have the intrinsic capability to reach the soul of black folks? Do the painting on the wall and the statue on the pedestal—traditional European constructs—have the same importance to blacks as they do to whites?

Photography and filmmaking have appealed to a wider audience, black and white alike. Perhaps because these are newer media, with shorter traditions, they are less culturally bound than are painting and sculpture. Their language and codes have been accessible to all people, irrespective of culture or race. The photography of James Van Der Zee, Roy DeCordova, and Gordon Parks has attracted a wider black audience. Noting the effectiveness of photography, other artists incorporated it into their work to achieve a wider audience. The artists who created The Wall of Respect and the members of Afri-Cobra used photographs as mass consumer imagery. Gordon Parks filmed the Shaft movies and showed a generation of black photographer’s new possibilities of lighting and color.

Filmmakers and actors such as Melvin Van Peebles, Sidney Poitier, and Harry Belafonte explored black humor in film and in turn fueled the creative spirit of a new generation of black film and TV makers. Spike Lee, John Singleton, Mario Van Peebles, and Bill Cosby have plunged into popular culture where they have found that black folks are ready to break down the boundary between art and entertainment. By combining these categories, black artists have created a new popular art. The new art finds the soul of black folk in the Spontaneous social mixture of the street, which creates a new dynamism. It is not crime they find there, but passion, which is free.

Artists Carrie Mae Weems and Pat Ward Williams work with photography, narrative, and installation, and draw their content from personal experience, history, and the hip life of the streets. Philip Mallory Jones’s video deals with African American popular issues. Langston Hughes said that black culture was in the lives of the down-home folk. Miles Davis searched for new pop melodies as a source for his jazz. When asked where jazz improvisation would end, Dizzy Gillespie supposedly said it would end where it had begun: with a man beating a drum. He meant that the essence of African American art was in its primal impetus, which is self-definition.

In the 1960s, artists learned that they are freed artistically more by political power than by any aesthetic development. During that decade, the white establishment gave black artists more play than ever before, not because the art had suddenly become better, but because they were afraid of black power. In the 1980s they stopped because they were no longer afraid. Today some artists empower themselves by creating a market (for example, filmmakers and pop musicians), and by making new alliances with black artists across the globe. The work of recent African American artists is not better than that of their predecessors, but it is freer. It is freer from Eurocentrism, as much as from ancient African art, even when it includes both. By declaring that there is no difference in quality between “high art” and entertainment, they have revealed that, at least for them, “profundity” is no more than a chimera, and “quality” no more than a cultural bias. How much like the postmodernists does this sound! But whose authorship is it? African Americans! What a great debt post- modernism owes to African American ideas! African Americans have joined a larger matrix of pan-African artists: people of African descent from many countries who now live in America. No longer is there just African American art, but a global presence of black artists in the United States. In the 1920s, Alain Locke called for artists to study the ancestral arts. He had traveled to Africa, collected African art, and wrote extensively on the subject. His vision of Africa was fora reunification of African peoples the world over. James A. Porter shared Locke’s views. From the 1940s through the early 1960s, Professor Porter, artist, writer, curator, brought many black artists from around the world to the United States, where he arranged exhibitions for them at the Howard University Art Gallery. Among the ones he brought were Brazil’s Candido Portinari, Cuba’s Wifredo Lam, Haiti’s Wilson Bigaud, Nigeria’s Ben Enwomwu. Porter traveled extensively in Africa, South America, and the Caribbean, researching the work of artists of African descent and writing about them. In 1951 he arranged the first exhibition of contemporary African art ever held in the United States, at the Howard University Art Gallery. Porter and his predecessor James Herring showed many white artists too (such as Morris Louis, Gene Davis, Kenneth Noland, David Smith). Their idea was to provide not only wider exposure for an international group of black artists, but to show that white artists could be integrated into an African-centered pantheon.

More recently, David Driskell has written on the influence of African ancestral art and has curated pan-African art exhibitions, such as Introspectives: Contemporary Art by Americans and Brazilians of African Descent (17). In the 1970s, Mary Schmidt Campbell, then director of the Studio Museum in Harlem, exhibited contemporary African artists together with African American artists. Her successor, Kinshasa Holman Conwill, has expanded the tradition to include art by people of color from several nations. In Los Angeles, Dr. Samella Lewis has pioneered in curating exhibitions that show relationships among African Americans, Caribbean people, South Americans, and Africans. Video artist Philip Mallory Jones curated the first globally touring collection of video art byAfrican diaspora artists in the summer of1994 (18).

Over the last twenty-five years, many white scholars have joined the cause of promoting artists of African descent. The National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., was founded by Warren Robbins. A part of Robbins’s philosophy was to show the relationship between the African ancestral arts and contemporary art by Africans and people of African descent worldwide (19). Equally significant is scholar Robert Farris Thompson. In his books and exhibitions, such as African Art in Motion and Flash of the Spirit, he has created a distinction between a true understanding of African art and the European perception of it as static anthropological icons. He has explored the concept of African art as a part of life and as a continuing presence in contemporary art in many exhibitions, lectures, and publications. Others such as Susan Vogel, director of the Museum for African Art in New York, John Nunley, Marilyn Houlberg, Judith Bettleheim, and the late Jean Kennedy-Wolford have re- sealed relationships between African art of the past and of today in various parts of the world.

Formalism has been the driving force in the evolution of modern art, but it has been far less of a preoccupation among African Americans than among whites (20). Perhaps this is because African Americans, having been kept outside the mainstream, searched for other ways to express themselves, and many of them dissolved the boundary between formal and folk art. These artists often work outside of Western pictorial traditions and improvised the style of their work to portray the black experience. William Edmundson, Sargent Johnston, William H. Johnson, Horace Pippin, and Minnie Evans are African American artists from the 1940s whose works are among the earliest examples of this movement. Edmundson, Pippin, and Evans were called “primitive.” Johnson and Johnston were formally trained artists, yet their mature styles have a directness often associated with folk art. They depicted some of the legends handed down by the slaves and the subjects of the spirituals. In African American art, trained and untrained artists often work in similar styles. The greater number of recognized American primitives are African American (21).

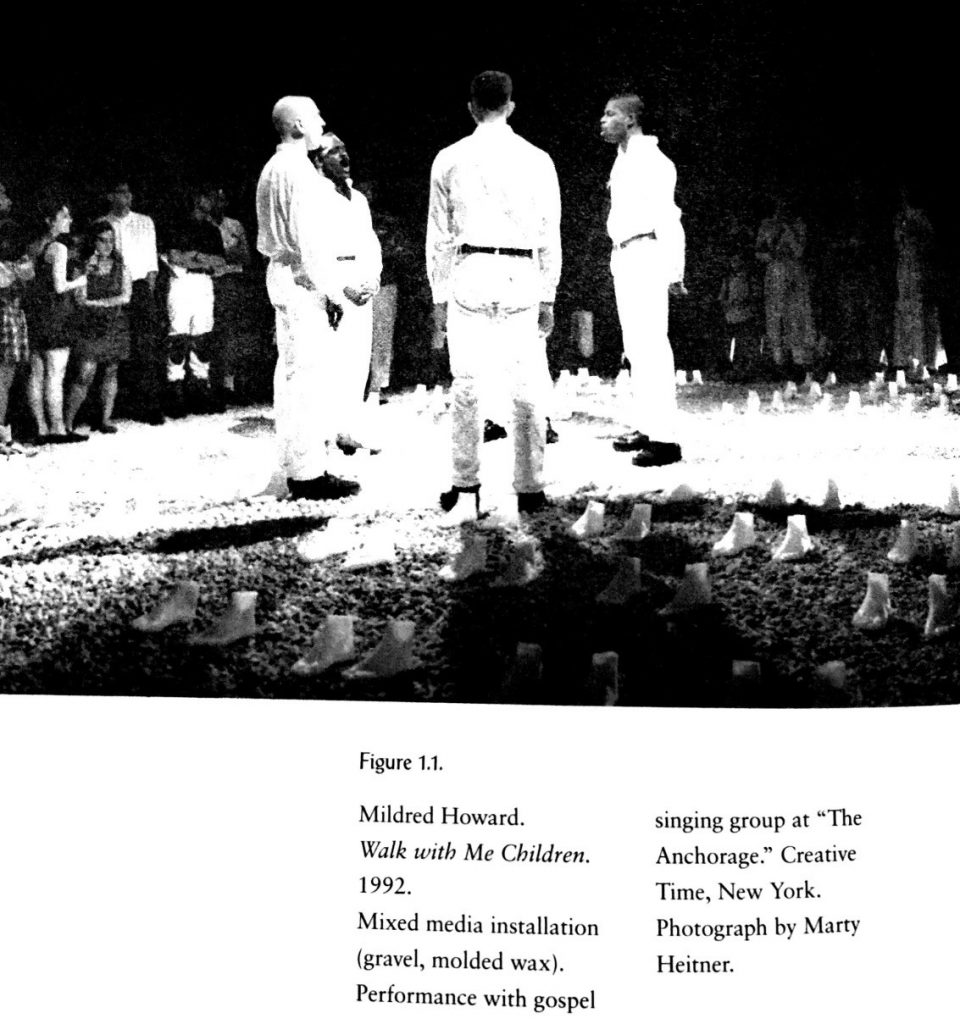

Contemporary artists such as Faith Ringgold, David Hammons, Lois Mailou Jones, Bettye Saar, Alison Saar, Frederick Brown have all bent the boundary between formal and informal art. Ringgold has made a large number of quilts that are decorated to reflect the themes of the spirituals. Martin Puryear’s handcrafted sculptures have biomorphic shapes and organic materials that mirror the world of nature. Performance artists Greg Leigon and Sherman Fleming focus on the black experience (22).

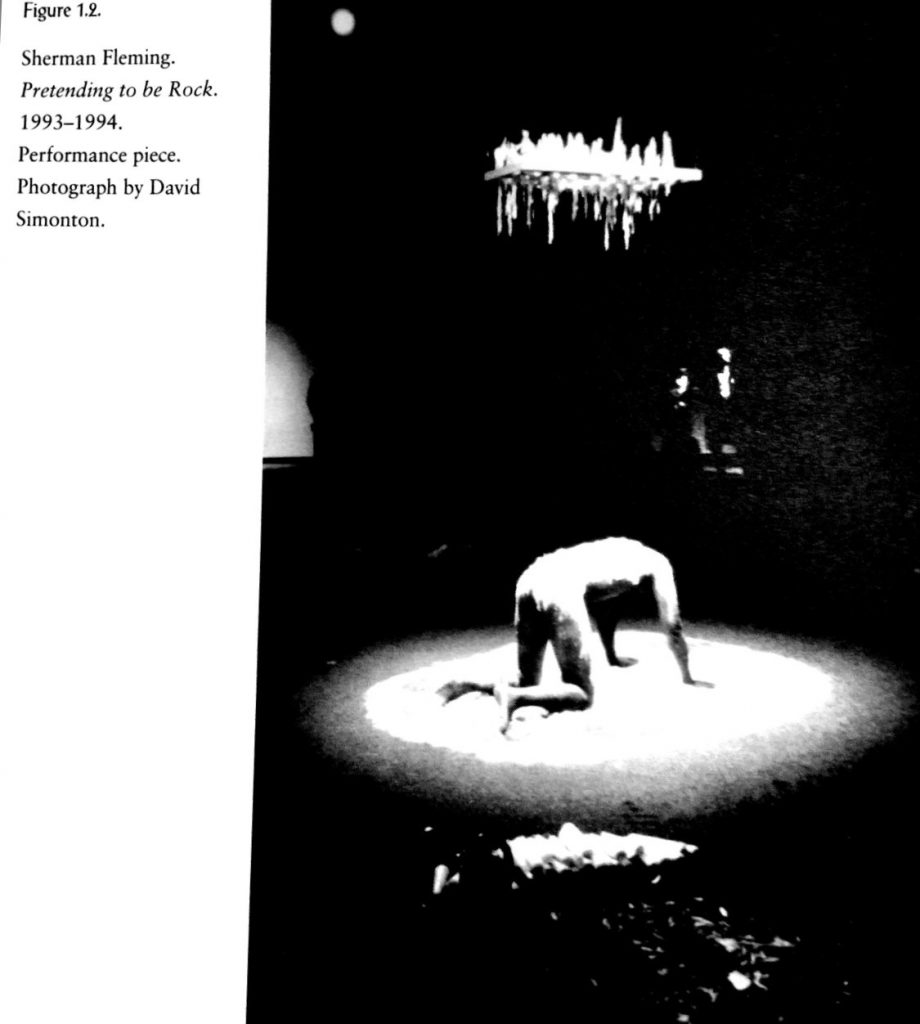

Fleming describes his performances as combining “childhood games, ritual dance actions, and quotidian gestures” within a “social matrix of racism and sexism” (fig. 1.2) (23). Cuban Wifredo Lam forged a style from cubism and surrealism, but his subjects come from African experiences. Quattara from the Ivory Coast places images of African figures, symbols, and architecture in a two-dimensional space (fig. 1.3). Haiti’s Rignaud Benoit explores African Caribbean myths and folklore. Edouard Duval-Carriè’s art combines primordial forms, African Caribbean ritual, and references to postcolonial politics (plate 6). Jamaica’s Kapo, who was a priest, created paintings and sculptures of figures that became icons of his African Carib- bean religion. Maren Hassinger’s environmental installations reveal her ability to merge designs from African architecture and hatchery into abstract art.

Like the fallen boundary between high art and popular entertainment, the collapse of the boundary between formal art and folk art has far-reaching implications. For African Americans, it furthers the cause of artistic equality. In the 1960s, Bob Thompson reinterpreted the principles of Renaissance art in ways that made people think of his work as “primitive.” He broke down the division between formal art and folk art by combining elements of both. David Hammons uses objects he finds among black people, such as bottle caps and barber shop hair, as emblems of black culture. Critic Judith Wilson feels that Hammons’s art is based on “radical egalitarianism. . . . [He is] disenchanted with Western materials. (24) Bettye Saar makes icons of found objects. Robert Colescott parodies formal art by substituting cartoon figures for classical heroes.

Other artists draw inspiration from the art of Africa. Emma Amos borders some of her paintings with Kente cloth. Faith Ringgold and Howardena Pindell explore their own biographies through quilts, beadwork, and sewn fabric. Martha Jackson-Jarvis uses ceramics to make sculpture that is reminiscent of ancient African artifacts recently unearthed or pulled from the bottom of the sea. Joyce Scott uses beads, metal armature, and found objects to create a mythology through imaginative artifacts that appear to come from ancient Africa through the era of slavery. Adrian Piper uses verbal expressions, advertising, and photo journalism to examine stereotypes about people of color.

Figure 1.3

Quattara

Gaia. 1994

Mixed media on wood. University Art Museum, University of California at Berkley. Gift of the artist

The recent immigration of millions has brought into the United States the greatest confluence of the African diaspora in history. Immigration is changing the definition of what it means to bean African American. Artists Skunder Boghossian (Ethiopia), Quattara (Ivory Coast), Juan Sanchez (Puerto Rico), and Kofi Kiyaga (Jamaica) live and work here, as do thousands of others. African artists Twins Seven—SevenandmLamedi Fakeye show and lecture across the country. The United States Information Agency’s international programs bring us artists from Haiti and South Africa. African and African American art journals are sharing information to a dramatic degree. A number of these people ofAfrican descent are inclined to combine the visual arts with music, dance, and ceremony. Yoruba practices, African altars, Caribbean ceremonies, and African Brazilian customs have become common from New York to Oakland. The exhibition and book Caribbean Festival Art, curated and written by Judith Bettelheim and John Nunley, explored the history of the festival and its origin among Africans in the Caribbean and the spread of its popularity to the United States and Canada (25). In Chicago, Mr. Imagination creates African American figures from bottle caps, wood, and nails that look like African icons (fig. 1.4). Also in Chicago, David Philpot, a self-trained artist, makes West African style canes that he decorates with snakes and other symbols of magical potency.

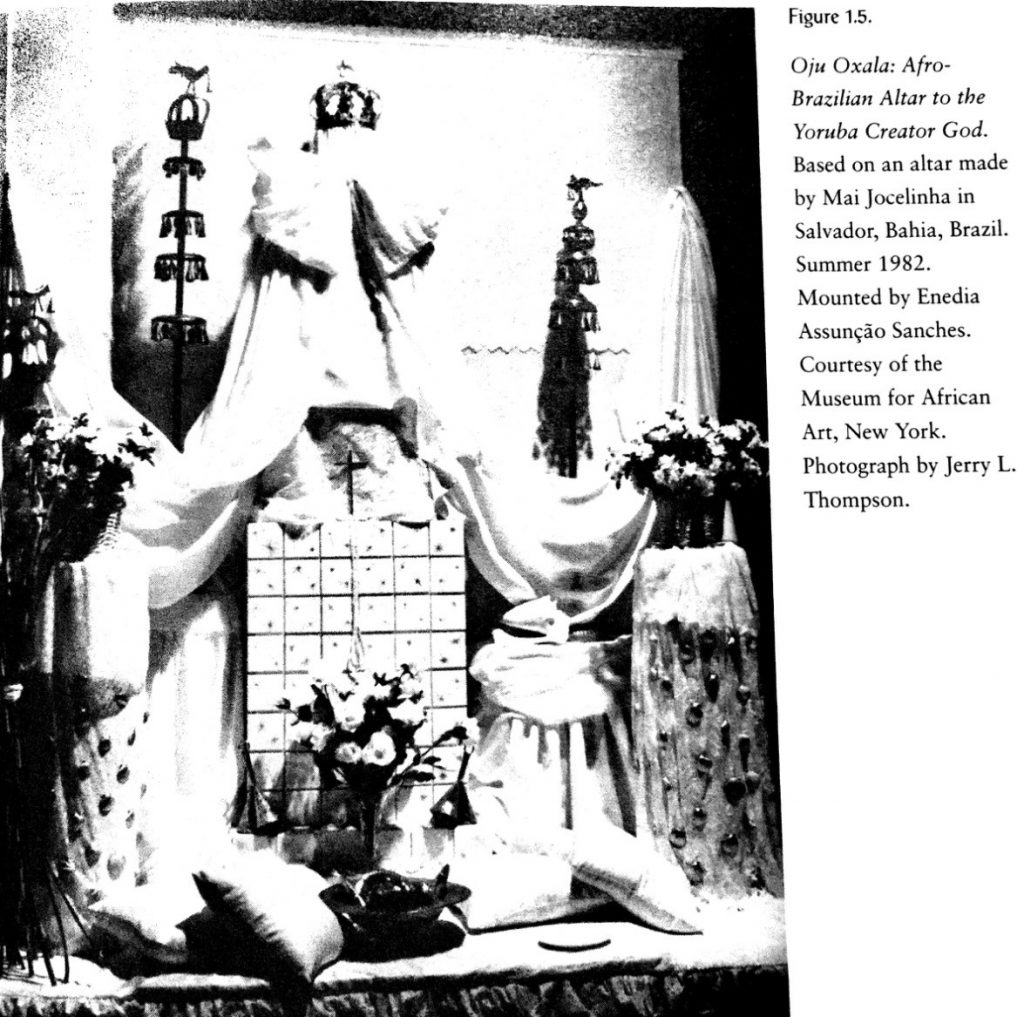

Artists of African descent all over the country are exploring shrines and altars. Rene’e Stout from Washington, DC, creates slave-like environments and shrines that evoke the spirits of her African ancestors. Robert Farris Thompson’s exhibition, Face of the Gods, presented 18 altars that linked West and Central African religious art to that of Brazil, Cuba, Haiti, Puerto Rico, and to peoples ofAfrican descent in North, Central, and South America (fig. 1.5) (26). His work is shown in New York as well as Haiti. Among his works recently shown in museums is an African Brazilian altar to the Yoruba creator god. Judith Bettelheim’s view on this installation sheds light on an important aspect of the new pan—African art:

How does one maintain belief in the face of centuries of suppression? How does one practice religion in the face of legal strictures against it? It must be realized that the practice of non institutionalized religion in America is/was in and of itself a revolutionary activity. It is often difficult for those of us educated in a European “avant-garde” tradition to view religious belief and expression as revolutionary, but in fact that is what developed in the Americas when the descendants of Africans creatively developed and practiced new religions under slavery and colonial repression. Some would even insist that, in some locations today, the contemporary practice of non institutionalized religions continues to be a rebellious, if not revolutionary, activity. And in some locations the practice of any religion is/was regarded as subversive. It is within this context that the altars included in this exhibition must be appreciated.

Sequins, lace,a faux leopard skin, doilies sprayed with gold paint, a quilted baby blanket, tops of feather dusters…strips of wooden beads from the seat covers that New York taxi drivers use, cement poured into sculptural forms, plastic flowers…objects that have been disassembled and reassembled to create installations crafted by the hands of practitioners, believers, survivors (27).

Figure 1.4

Ron Gordon.

Portrait of Mr. Imagination. 1991

Historians Thompson, Vogel, Robbins, Bettelheim, Nunley, Houlberg, and Drewal join the family of the diaspora in the United States. Pan-Africanism is more than a concept of race; it is the collective celebration of African culture the world over by black people especially, but also by others who are dedicated to the African experience. Celebration of pan-African ideas also comes from artists of other color, such as Vietnamese American Trinh T. Minh-ha, who worked in Africa and whose films and writings reflect the African sensibility. Christine Choi makes documentaries in Africa, New York, and Los Angeles about issues that are of importance to blacks. African Americans and their adopted brethren are linked across continents less by postmodernism than by a common pan-African experience.

In this collective, seemingly disparate people share three things: They are intrigued by issues of color (not necessarily their own), they are inspired by the African legacy, and they are committed to the art of the outsider. The source of their interest is the excitement created by the recent arrival of blacks from South America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia, who bring their various hues and cultural allegiances with them. The bond of these people of color seems to be Africa, not only because many share this legacy, but because African Americans have paved a path for universal cultural redemption through their telling of the African story. A Chinese American artist told me that a group of his people, after months of trying to define a strategy for their own cultural redemption, came to recognize that the best one was the strategy of the African American artists of the 1960s. Organizations of women artists (who have been mostly white) were among the first to take much of their rhetoric from African American artists.

Yet whatever their origin or gender, as they meld and join political common cause under the ever—widening umbrella of “people of color,” white artists seem to be moving inexorably away from the old American polemic of black versus white.

Americans are beginning to see themselves as people of different hues and ethnic groups (28). The old racial labels of black, white, and yellow don’t seem to stick anymore. Color is becoming a descriptive term: an adjective to describe differences in hue, rather than a noun to describe a race. As color distinctions proliferate, white may become not a race apart, but another color among many. But will this eliminate racism in America? The likely answer is no, since without a massive redistribution of wealth (not to happen soon) people of color will remain the poorest. By virtue of being poor—and disenfranchised—artists of color likely will continue to work outside of the art establishment for the foreseeable future. The driving force, then, of much American art inevitably may become African American ideas, albeit by misfortune. “African American” may become a political term rather than a racial one. “White” should also be a political term since there is no scientific way to establish whiteness by looking at someone (29).

A major difference between African American and Euro-American artists is that the former knows their politics is racial, while the latter claim that their politics is economical (30). Although the two propositions are not mutually exclusive, the African American one gets specifically to the heart of the down trodden, who believe that poverty is not the cause of racial bias but the result. African American art proponents establish their case by the evidence of the relationship between their color and their disenfranchisement. To the many who are inspired by African American art, be they people of color from Ghana, India, Korea, or Brazil—or be they white women or white men—the reason for their empathy is not the African blood that may or may not flow in their veins, nor is it their love of black people, to whom they may be indifferent, but it is the heroic example of the African American art that serves as a symbol of indomitable will to construct cultural survival in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. That is the gift of African American art to the future. This is its postmodernist beacon.

Notes

- Judith Wilson, “Seventies into Eighties.- Neo-Hoodism vs. Postmodernism,” The Decade Show (New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1990), 130—31.

- Thomas McEvilley, Fusion: West African Artists at the Venice Biennale (New York: Museum for African Art, 1993).

- Race has been the defining factor among people throughout American history. The nation’s first statute to establish requirements for citizenship, passed in 1790, limited naturalization to “aliens being free white persons.” Although amended to grant citizenship to blacks during the Civil War, the law stood until 1952. Many nonwhites, including Indians andJapanese, found it necessary to try to prove they were white until 1952.

- The definition of black was not always specific. For example in the nineteenth century, free mulattos were not considered black. Before the Civil War, several Southern states allowed people of mixed black and white ancestry to define themselves. After the Civil War, Southern whites passed laws that lowered and ultimately decreased to zero the percentage of black blood a white person could have. By 1924 legislators in Virginia prohibited whites from marrying anyone with “a single drop of Negro blood.” Other states in the South as well as the North followed suit.

- Henry Tanner (1859—1937). Other early African American artists such as Edmonia Lewis (1845—ca. 1890) andAugusta Savage (1892—1962), will be discussed later.

- Richard Hunt has long been a collector of Wes tAfrican metal works and sculpture.

- Barbara Chase—Riboud has been active since the late 19505. Today she works in the United States and France.

- Even before the abolition of slavery,the United States government had made plans to return blacks to Africa. After abolition, blacks returned to Africa, especially to Liberia, which was founded by African Americans. The concept of Africa as the original center of black American culture had been explored by many earlier artists, but interest reached a peak in the 1920s.

- See Keith Morrison, “Art Criticism: A Pan—African Point of View,” New Art Examiner 6, no.5 (January 1979): 4-7.

- Alain Leroy Locke (1896—1954) was a Harvard graduate and the first black Rhodes Scholar. He became a professor of aesthetics and philosophy at Howard University. He was also the editor of Crisis magazine, published by the NAACP, and was the most respected black critic of the 1920s and 1930s. In the Crisis, Locke wrote an essay entitled “The New Negro” in which he called upon black artists the African ancestral arts as a basis for an African American cultural ideology.

- More Stately Mansions is a mural that Douglas painted in the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library.

- Jacob Lawrence has said that he did not consciously imitate the flat space of Egyptian art because he taught himself how to paint, and he defined space according to a personal system. Nevertheless, his teacher at the Harlem Workshop, Charles Alston, knew of the theories of Locke and Douglas.

- The work takes its name from the so-called black national anthem written by James Weldon Johnson.

- For a good overview of the period, see Eva Cockcroft, John Weber, and James Cockcroft, Toward a Peoples’ Art (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977).

- Fred Hampton, a member of the Black Panther Party, and others were murdered in their sleep by gunfire from Chicago police.

- Created in 1988 as a commission for The Blues Aesthetic (Washington Project for the Arts,Washington,DC.) this painting was controversial among some African Americans who misunderstood its ironic intent.

- Henry Drewal and David C. Driskell, Introspectives: Contemporary Art by Americans and Brazilians of African Descent (Los Angeles: California Afro—American Museum, 1989).

- Philip Mallory Jones’s touring exhibition of video traveled from California to New York City, Havana, Rio, London, Paris, Berlin, Nairobi, Dakar, Abidjan, and Ouagadougou.

- Robbins turned the museum over to the Smithsonian in 1979. The Smithsonian lost sight of Robbins’s desire to show such relationships when it took over the African museum and relegated the African American portion of the collection to the Museum of American Art. Only in the last two years has the Museum of African Art begun to exhibit art by contemporary African artists. As one African artist asked: “Why does European history continue today, while mine is thought to have died in the nineteenth century?”

- It has never been all-pervasive, since modernist artists such as Ben Shahn, Joseph Cornell, Leon Golub, Harry Westerman, Julius Schmidt, and Roger Brown developed non—formalist art, as have a range of funk artists and groups such as the “Hairy Who,” but they have been additions—albeit important ones—to the mainstream of modern American art, rather than the driving forces behind it. Others such as Grandma Moses, Edward Hicks, and John Kane, all called “primitive,” have, of course, been important in American art.

- This fact has been documented by several books and exhibitions on the subject. African American artists such as Horace Pippin, Sister Gertrude Morgan, James Hampton, Joseph Yoakum, and William Edmundson are only a few of the many recognized primitives in American art.

- Greg Leigon is one of a growing number of artists who are exploring aspects of gay culture in black America.

- Sherman Fleming, who has made art individually and with groups over the years,

performs under the names RODFORCE and Generator Exchange.

- Wilson, “Seventies into Eighties,” 133.

- Judith Bettelheim and John Nunley, Caribbean Festival Art (Seattle: St. Louis Art Museum and University of Washington Press, 1988).

- Robert Farris Thompson, Face of the Gods: Art (Munich and New York: Prestel and

the Museum for African Art, 1993).

- Judith Bettelheim, “Face of the Gods,” Art Journal 153, no. 2 (summer 1994): 100.

- According to the 1990 census, Americans claimed membership in nearly 300 races or ethnic groups and 600 Native American tribes.

- Tom Morganthau,“What Color Is Black?” Newsweek 125, no. 7 (February 13,

1995): 62—72. Morganthau states that race has practically no meaning in terms of color. According to scientists quoted in the article, the dark—skinned Somalis, for example, are no more related genetically to the Ghanaians than they are to the Greeks. Some scientists point out that the notion and specifics of race predate genetics, evolutionary biology, and the science of human origin.

- I am not prepared to argue the Euro-American case.

Bibliography

Bettelheim, Judith, and John Nunley. Caribbean Festival Art. Seattle: St. Louis Art Museum and University ofWashington Press, 1988.

Bettelheim, Judith. “Face of the Gods.” Art Journal 53, no. 2 (summer 1994): 100.

Campbell, Mary Schmidt, David Driskell, and Cedric Dover. American Negro Art. New York: New York Graphic Society, 1960.

Cervantes, Miguel. Mitoy Magiaen America: Los Ochentos. Monterey, Mexico: Museum of Modern Art, 1991.

Cockcroft, Eve, John Weber, and James Cockcroft. Toward a People’s Art. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977.

Debela, Acha, and Kenneth Rogers. Afri-Cobra. Eastern Shore, Md.: Mosley

Gallery of Art, University of Maryland, 1984.

Drewal, Henry, and David C. Driskell. Introspective: Contemporary Art by

Americans and Brazilians of African Descent. Los Angeles: California Afro- American Museum, 1989.

Dyson. Michael. Reflecting Black. Minneapolis, Minn.: University ofMinnesota Press,

Kennedy, Jean. New Currents, Ancient Rivers. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992.

Lewis, David Levering, and Deborah Willis Ryan. Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black

America. New York: Studio Museum in Harlem and Harry N. Abrams,1987.

Lippard, Lucy. Mixed Blessings: New Art in a Multicultural America. New York: Pantheon Books, 1990.

McEvilley, Thomas. Fusion: West African Artists at the Venice Biennale. New York.-

Museum for African Art, 1993.

Morganthau, Tom. “What Color Is Black?” Newsweek 125, no. 7 (February 13,

1995): 62—72.

Morrison, Keith. “Art Criticism: A Pan—African Point ofView.” New Art Examiner 6

(January 1979): 4—7.

New Museum of Contemporary Art, Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, and Studio Museum in Harlem. Decade Show: Frameworks for Identity in the 1980s. New Museum of Contemporary Art, Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, and Studio Museum in Harlem, 1990. Porter, James A. Modern Negro Art. 1943. Reprint, Washington,DC:Howard University Press, 1992.

Powell, Richard. The Blues Aesthetic. Washington, DC: Washington Project for the Arts, 1989.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Face of the Gods: Art. Munich andNew York: Prestel and Museum forAfrican Art, 1993.